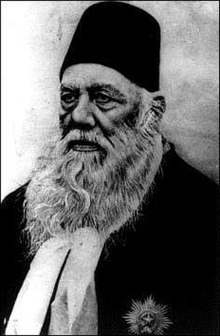

Syed Ahmad Taqvi bin Syed Muhammad Muttaqi[1] KCSI (Urdu: سید احمد خان; 17 October 1817 – 27 March 1898), commonly known as Sir Syed Ahmad Khan (also Sayyid Ahmad Khan), was an Islamic pragmatist,[2] Islamic reformer,[3][4] philosopher, and educationist[5] in nineteenth-century British India.[6][7] Though initially espousing Hindu-Muslim unity, he became the pioneer of Muslim nationalism in India and is widely credited as the father of the two-nation theory, which formed the basis of the Pakistan movement.[8][9][10][11] Born into a family with strong debts to the Mughal court, Ahmad studied the Quran and Sciences within the court. He was awarded an honorary LLD from the University of Edinburgh in 1889.[12][9][7]

In 1838, Syed Ahmad entered the service of East India Company and went on to become a judge at a Small Causes Court in 1867, retiring from 1876. During the War of Independence of 1857, he remained loyal to the British Raj and was noted for his actions in saving European lives.[3] After the rebellion, he penned the booklet The Causes of the Indian Mutiny – a daring critique, at the time, of various British policies that he blamed for causing the revolt. Believing that the future of Muslims was threatened by the rigidity of their orthodox outlook, Sir Ahmad began promoting Western–style scientific education by founding modern schools and journals and organising Islamic entrepreneurs.

In 1859, Syed established Gulshan School at Muradabad, Victoria School at Ghazipur in 1863, and a scientific society for Muslims in 1864. In 1875, founded the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, the first Muslim university in Southern Asia.[13] During his career, Syed repeatedly called upon Muslims to loyally serve the British Raj and promoted the adoption of Urdu as the lingua franca of all Indian Muslims. Syed criticized the Indian National Congress.[14]

Syed maintains a strong legacy in Pakistan and among Indian Muslims. He strongly influenced other Muslim leaders including Allama Iqbal and Muhammad Ali Jinnah. His advocacy of Islam's rationalist tradition, and at broader, radical reinterpretation of the Quran to make it compatible with science and modernity, continues to influence the global Islamic reformation.[15] Many universities and public buildings in Pakistan bear Sir Syed's name.[16]

Aligarh Muslim University celebrated Sir Syed’s 200th birth centenary with much enthusiasm on 17 October 2017. Former President of India Pranab Mukherjee was the chief guest.[17][18]

Early life

Syed Ahmad Taqvi 'Khan Bahadur' was born on 17 October 1817 in Delhi, which was the capital of the Mughal Empire in the ruling times of Mughal Emperor Akbar II. Many generations of his family had since been highly connected with the administrative position in Mughal Empire. His maternal grandfather Khwaja Fariduddin served as Wazir (lit. Minister) in the court of Emperor Akbar Shah II.[19] His paternal grandfather Syed Hadi Jawwad bin Imaduddin held a mansab (lit. General)– a high-ranking administrative position and honorary name of "Mir Jawwad Ali Khan" in the court of Emperor Alamgir II. Sir Syed's father, Syed Muhammad Muttaqi,[20] was personally close to Emperor Akbar Shah II and served as his personal adviser.[21]

However, Syed Ahmad was born at a time when his father was regional insurrections aided and led by the East India Company, which had replaced the power traditionally held by the Mughal state, reducing its monarch to figurehead. With his elder brother Syed Muhammad bin Muttaqi Khan, Sir Syed was raised in a large house in a wealthy area of the city. They were raised in strict accordance with Mughal noble traditions and exposed to politics. Their mother Aziz-un-Nisa played a formative role in Sir Syed's early life, raising him with rigid discipline with a strong emphasis on modern education.[22] Sir Syed was taught to read and understand the Qur'an by a female tutor, which was unusual at the time. He received an education traditional to Muslim nobility in Delhi. Under the charge of Lord Wellesley, Sir Syed was trained in Persian, Arabic, Urdu and orthodox religious subjects.[23] He read the works of Muslim scholars and writers such as Sahbai, Rumi and Ghalib.[citation needed] Other tutors instructed him in mathematics, astronomy and Islamic jurisprudence.[24][25] Sir Syed was also adept at swimming, wrestling and other sports. He took an active part in the Mughal court's cultural activities.[26]

Syed Ahmad's elder brother founded the city's first printing press in the Urdu language along with the journal Sayyad-ul-Akbar.[citation needed] Sir Syed pursued the study of medicine for several years but did not complete the course.[24] Until the death of his father in 1838, Sir Syed had lived a life customary for an affluent young Muslim noble.[24] Upon his father's death, he inherited the titles of his grandfather and father and was awarded the title of Arif Jung by the emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar.[27] Financial difficulties put an end to Sir Syed's formal education, although he continued to study in private, using books on a variety of subjects.[26] Sir Syed assumed editorship of his brother's journal and rejected offers of employment from the Mughal court.[26]

Career

Having recognized the steady decline in Mughal political power, Sir Syed decided to enter the service of the East India Company. He could not enter the colonial civil service because it was only in the 1860s that Indians were admitted.[28] His first appointment was as a Serestadar (lit. Clerk) at the courts of law in Agra, responsible for record-keeping and managing court affairs.[28] In 1840, he was promoted to the title of munshi. In 1858, he was appointed to a high-ranking post at the court in Muradabad, where he began working on his most famous literary work.

Acquainted with high-ranking British officials, Sir Syed obtained close knowledge about British colonial politics during his service at the courts. At the outbreak of the Indian rebellion, on 10 May 1857, Sir Syed was serving as the chief assessment officer at the court in Bijnor.[citation needed] Northern India became the scene of the most intense fighting.[29] The conflict had left large numbers of civilians dead. Erstwhile centres of Muslim power such as Delhi, Agra, Lucknow and Kanpur were severely affected. Sir Syed was personally affected by the violence and the ending of the Mughal dynasty amongst many other long-standing kingdoms.[citation needed] Sir Syed and many other Muslims took this as a defeat of Muslim society.[30] He lost several close relatives who died in the violence. Although he succeeded in rescuing his mother from the turmoil, she died in Meerut, owing to the privations she had experienced.[29]

Social reforms in the Muslim society were initiated by Abdul Latif who founded "The Mohammedan Literary Society" in Bengal. Sir Syed Ahmad Khan established the MAO College which eventually became the Aligarh Muslim University. He opposed ignorance, superstitions and evil customs prevalent in Indian Muslim society. He firmly believed that Muslim society would not progress without the acquisition of western education and science. As time passed, Sir Syed began stressing on the idea of pragmatic modernism and started advocating for strong interfaith relations between Islam and Christianity.

Causes of the Indian Revolt

Sir Syed supported the East India Company during the 1857 uprising, a role which has been criticised by some nationalists such as Jamaluddin Afghani. In 1859 Sir Syed published the booklet Asbab-e-Baghawat-e-Hind (The Causes of the Indian Revolt) in which he studied the causes of the Indian revolt. In this, his most famous work, he rejected the common notion that the conspiracy was planned by Muslim elites, who resented the diminishing influence of Muslim monarchs. He blamed the East India Company for its aggressive expansion as well as the ignorance of British politicians regarding Indian culture. Sir Syed advised the British to appoint Muslims to assist in administration, to prevent what he called ‘haramzadgi’ (a vulgar deed) such as the mutiny.[31]

Maulana Altaf Hussain Hali wrote in the biography of Sir Syed that:

"As soon as Sir Syed reached Muradabad, he began to write the pamphlet entitled 'The Causes of the Indian Revolt' (Asbab-e-Baghawat-e-Hind), in which he did his best to clear the people of India, and especially the Muslims, of the charge of Mutiny. In spite of the obvious danger, he made a courageous and thorough report of the accusations people were making against the Government and refused the theory which the British had invented to explain the causes of the Mutiny."[32]

When the work was finished, without waiting for an English translation, Sir Syed sent the Urdu version to be printed at the Mufassilat Gazette Press in Agra. Within a few weeks, he received 500 copies back from the printers. One of his friends warned him not to send the pamphlet to the British Parliament or to the Government of India. Rae Shankar Das, a great friend of Sir Syed, begged him to burn the books rather than put his life in danger. Sir Syed replied that he was bringing these matters to the attention of the British for the good of his own people, of his country, and of the government itself. He said that if he came to any harm while doing something that would greatly benefit the rulers and the subjects of India alike, he would gladly suffer whatever befell him. When Rae Shankar Das saw that Sir Syed's mind was made up and nothing could be done to change it, he wept and remained silent. After performing a supplementary prayer and asking God's blessing, Sir Syed sent almost all the 500 copies of his pamphlet to England, one to the government, and kept the rest himself.

When the government of India had the book translated and presented before the council, Lord Canning, the governor-general, and Sir Bartle Frere accepted it as a sincere and friendly report. The foreign secretary Cecil Beadon, however, severely attacked it, calling it 'an extremely seditious pamphlet'. He wanted a proper inquiry into the matter and said that the author, unless he could give a satisfactory explanation, should be harshly dealt with. Since no other member of the Council agreed with his opinion, his attack did no harm.

Later, Sir Syed was invited to attend Lord Canning's durbar in Farrukhabad and happened to meet the foreign secretary there. He told Sir Syed that he was displeased with the pamphlet and added that if he had really had the government's interests at heart, he would not have made his opinion known in this way throughout the country; he would have communicated it directly to the government. Sir Syed replied that he had only had 500 copies printed, the majority of which he had sent to England, one had been given to the government of India, and the remaining copies were still in his possession. Furthermore, he had the receipt to prove it. He was aware, he added, that the view of the rulers had been distorted by the stress and anxieties of the times, which made it difficult to put even the most straightforward problem in its right perspective. It was for this reason that he had not communicated his thoughts publicly. He promised that for every copy that could be found circulating in India he would personally pay 1,000 rupees. At first, Beadon was not convinced and asked Sir Syed over and over again if he was sure that no other copy had been distributed in India. Sir Syed reassured him on this matter, and Beadon never mentioned it again. Later he became one of Sir Syed's strongest supporters.

Many official translations were made of the Urdu text of The Causes of the Indian Revolt. The one undertaken by the India Office formed the subject of many discussions and debates.[33] The pamphlet was also translated by the government of India and several members of parliament, but no version was offered to the public. A translation which had been started by a government official was finished by Sir Syed's great friend, Colonel G.F.I. Graham, and finally published in 1873.[32]

Influence of Mirza Ghalib

In 1855, he finished his scholarly, well researched and illustrated edition of Abul Fazl's Ai'n-e Akbari, itself an extraordinarily difficult book. Having finished the work to his satisfaction, and believing that Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib was a person who would appreciate his labours, Syed Ahmad approached the great Ghalib to write a taqriz (in the convention of the times, a laudatory foreword) for it. Ghalib obliged, but what he did produce was a short Persian poem castigating the Ai'n-e Akbari, and by implication, the imperial, sumptuous, literate and learned Mughal culture of which it was a product. The least that could be said against it was that the book had little value even as an antique document. Ghalib practically reprimanded Syed Ahmad Khan for wasting his talents and time on dead things. Worse, he praised sky-high the "sahibs of England" who at that time held all the keys to all the a’ins in this world.[34]

The poem was unexpected, but it came at the time when Syed Ahmad Khan's thought and feelings themselves were inclining toward change. Ghalib seemed to be acutely aware of a European[English]-sponsored change in world polity, especially Indian polity. Syed Ahmad might well have been piqued at Ghalib's admonitions, but he would also have realized that Ghalib's reading of the situation, though not nuanced enough, was basically accurate. Syed Ahmad Khan may also have felt that he, being better informed about the English and the outside world, should have himself seen the change that now seemed to be just round the corner.

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan never again wrote a word in praise of the Ai'n-e Akbari and in fact gave up taking an active interest in history and archaeology. He did edit another two historical texts over the next few years, but neither of them was anything like the Ai'n: a vast and triumphalist document on the governance of Akbar

Reviewed by Janaan Films Team

on

August 12, 2021

Rating:

Reviewed by Janaan Films Team

on

August 12, 2021

Rating:

No comments: